The presidential debates got me thinking about the situation with student debt. I asked myself “What do the financial crisis of 2008 and our current problems with higher education debt have in common?” I thought of two foundational flaws:

-

Extremely easy access to credit

-

The belief that the borrowed funds from above are being used to buy an asset that cannot go down in value

Let’s start with easy access to credit. Before the financial meltdown of 2008, mortgages were incredibly easy to get. Insanely easy. Like you didn’t need to prove you were employed easy. You could get one mortgage for 90% of the value of the house you were buying and then get a second mortgage for the other 10%. These mortgages came at a cost, namely high or variable interest rates.

Since everyone had access to an almost endless amount of credit, housing prices exploded, which led to higher mortgages on assets with inflated values. This also allowed those who owned homes to take out ridiculous lines of credit or 2nd mortgages on their homes because the value of their houses skyrocketed.

Eventually when it came time to pay for all this borrowing, surprisingly, most borrowers couldn’t pay. Which caused a market whiplash to happen – house values suffered steep declines, borrowers now owed more than their assets were worth so they either walked away or tried to sell at much lower prices, which caused home values to decline more, which caused more people to panic, etc…Until the whole global financial system came within hours of completely collapsing.

Now compare that to what we have seen in higher education of the last 10-15 years. The federal government will give anyone a loan for college. Fill out some paperwork and the government will loan you money for school. In most cases they are lending money to a 17 or 18-year-old kid, with no credit history, no assets, no real work experience, and no real way to ever pay back the loan. But why let financial reality stand in the way loose lending policies.

Think of this from the college and university perspective. They have customers (students) who have unlimited access to money (and that money is backed by the federal government, so the schools have zero risk) which increases the demand for higher education because there is no financial barrier and allows colleges and universities to raise their prices. And raise them. And raise them. And raise them. They have no reason to stop raising prices because the federal government will always loan money to 18-year-old kids to cover the cost of higher education.

The challenge here is that students can’t walk away from their student debt. You can’t choose to not pay it. You can’t even declare bankruptcy to get rid of it (bankruptcy doesn’t absolve what you owe for student loans). So now we have a generation that has vastly overpaid for an asset (college degree) that isn’t worth the debt that is owed on it.

The second part is the belief that the underlying asset will never go down in value. Before 2008 there was the universal belief that homes would NEVER go down in value. This assumption was the reason for all the mortgage nonsense. This assumption was proven catastrophically wrong leading to the worst recession in our country’s history and that many parts of our economy have not (and may never) recovered from.

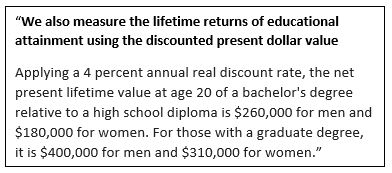

This same incorrect assumption is fueling student debt. I’ve been told “once you have an education, they can’t take it away from you” or “you have to go to college”. I’ve read countless articles about how people with a bachelor’s degree earn $900,00+ more in their life than those with just a high school diploma. But what if the cost doesn’t equal the value? This is from the Social Security office:

In today’s dollars, a bachelor’s degree is worth an extra $260,000 for men. Now let’s say you paid $40,000 out of pocket (no loans) a year to earn that 4-year degree. That’s $160,000 in today’s dollars. So you net $100,000 ($260,000 – $160,000) in value. As we all know, $100,000 isn’t going very far.

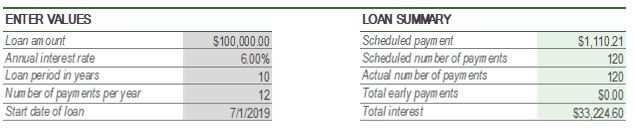

Now think if you couldn’t pay out of pocket and you had to borrow money to pay for school. We’ll say you could pay $60,000 out of pocket, but had to borrow $100,000 at 6% for 10 years.

Now the student is paying over $33,000 in interest, plus they have a monthly payment of $1,110. What does that monthly payment actual mean in the real world? According to the Bureau of Labor Statistics, a person with a bachelor’s degree earns $1,173 a week. That is $61,000 gross per year. The student would pay $13,325 in student debt payments. That is ~22% of the students’ gross pay (and over 26% of net pay).

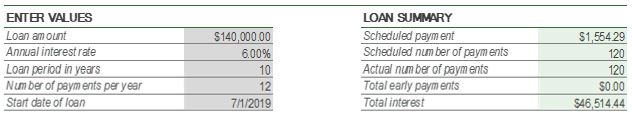

What if you had to take out $140,000 in loans?

Students are paying over 35% of their pay to cover their student debt.

Keep in mind that all of this is happening with record low unemployment. If there is even a small rise in unemployment, that could be disastrous for so many with overbearing student debt.

Much like people paying $1,000,000 for a $350,000 home just because they could get a mortgage, students are forced to pay $150,000 for a $25,000 higher education just because the government will loan them money.

What’s the fix? Forgive all the student debt that is on the federal government’s books as suggested by Bernie Sanders? I think that’s a bit much. One of the fixes after the financial meltdown was the federal government allowed homeowners to remortgage their homes at a more realistic value. I think the federal government could do something along those lines for student loans (based on degree and income levels).

But in order to fix the problem, the federal government needs to get out of the student loan business. Turn off the money.

What will happen? Enrollment would immediately plummet, and colleges and universities would need to cut back on expenses (or dip into their enormous, untaxed endowments). Some (or many) subpar colleges and universities would close, the schools that can weather the storm will be forced to compete for students by offering a better education and a better experience. Schools will then need to significantly reduce the cost of attendance. There will be premium brand schools and everyday brands, but the cost will reflect the ability of students to pay. Schools can look to get into the lending business, banks can get more involved in the student lending business, but it won’t be a free for all, these institutions will be much more risk averse and take measures to protect themselves and the students from becoming buried in debt.

Or we can do nothing and wait for the whole system to collapse and then, much like when we bailed out Wall Street, we can all pay to bail out Harvard.